| POTTSTOWN MERCURY, Pottstown, PA., Thursday,

February 23, 1961 Dentists Pull Teeth,

Clowns Act Up in Old Penny Banks

(Editor’s Note: Mr. and Mrs. William Roup, of

301 Grandview Road, collect old American toys – in particular, mechanical

penny banks and horse drawn carriages. This is the first in a series of

articles on their collection – one of the most complete in America.)

The toy banks of yesterday can be compared to the cartoon of today –

sometimes funny, sometimes tender, sometimes an insight into America itself.

Place a coin in a Dentist’s bank, and the dentist yanks away on the

patient’s tooth, the tooth comes out, the patient falls back out of the

chair – and the coin disappears.

Place a coin in the Harlequin bank and the three sad figures of

traditional English pantomime – the clown, the columbine and the Harlequin –

begin what seems to be a last farewell dance.

Place a coin on a plank labeled monopoly and it is sledge-hammered

off into the rich man’s barrel by an over-burdened worker.

More than just a bank?

“Not really,” say the Roups, “but just an example of an art that no

longer exists – an art that made saving just as profitable as it is today,

but twice as much fun.”

* *

*

THE ROUPS should know. Two of the foremost collectors of the

mechanical penny banks – and other old American toys – in the United States,

they now have over 150 of the small cast iron coin collectors in the white

paneled basement of their home.

They began their collection some 15 years ago when they discovered an

Elephant bank in an antique shop. “We were fascinated with it,” Mrs. Roup

enthused. “You placed the penny near the elephant’s trunk, and when an

acrobat twitched his tail, the trunk swung from side to side, knocking the

coin into the base of the bank.”

The Roup’s discovery in an antique shop came at the same time the

collecting of old penny banks began to mushroom in the United States. Roup

estimates that “there are probably thousands of old toy collectors in the

United States, and at least 100 who just specialize in mechanical penny

banks.”

The “hotbed” of mechanical penny bank collecting is in Pennsylvania,

New York, and Connecticut, but the Roups keep up a coast to coast

correspondence with other collectors and dealers.

* *

*

THEY CAN’T really be called antiques, because the mechanical banks

are not yet 100 years old. The oldest date from 1869 and they were still

being made in the early 1900s. The latest in their collection is a 1921

model in which a penny makes a doll baby in an eggshell cry.

The Roups say three things fascinate them most about the mechanical

marvels. “First, they were all designed for pennies, second they work with

hair trigger precision and thirdly, not only were they designed to save

money, but to be enjoyed,” Roup explains.

“Mostly, though, I guess we just enjoy collecting them,” Mrs. Roup

explained.

But at least once the enjoyment turned into near horror. The Roups

own a bank called the Presto – the only one of its kind known to still

exist.

Roup removed one screw from the back of the bank to clean it and the entire

thing collapsed – into 28 watch-like parts.

“We just sat there staring at it in horror,” Mrs. Roup remembered.

“Luckily we had the original pattern papers and with the help of a trained

mechanic were able to put it back. But for a while we were in a state of

shock that bordered on near panic.”

Other Presto banks were made in tin, but the Roups’ is the only one

in iron. Insert a penny in the cash register shaped box and when it hits the

bottom, you look through a peep hole in the back and see that it’s turned

into a quarter.

“It’s done with mirrors, naturally,” Roup explains, “but the motto on

the front explains its purpose: ‘We offer aid to all who strive to make one

penny twenty-five.”

* *

*

THE BANKS originally sold for $8 a dozen, but were reduced to $2 a

dozen a year after they were placed on the market in 1886. “Evidently didn’t

sell too well,” John D. Meyer reported in a “Handbook of Old Mechanical

Banks.”

He also added that “To date none of these has been found,” but agreed

to delete that statement in his next book after seeing the Roups’ Presto

bank. “I guess one has been found.”

While the Presto bank is the rarest, the Harlequin is the most

popular “probably because of the action and the fact that it is so much fun

to look at.”

The three sad figures seem no sadder than Meyer. In his book he says:

“I can’t help saying ‘I wish I had this bank,’ but maybe sometime.”

“He won’t get it from us,” the Roups vow.

It was fun to save

in the old days, and for Mr. and Mrs. William Roup, of 301 Grandview Road,

it is still fun. The Roups have one of America’s most complete collection of

mechanical penny banks – including the Harlequin, shown in the picture with

Roup. When a penny is inserted, three tragic figures of English pantomime

dance around each other.

The Roups have more than 150 of the banks – including those pictured.

Those in the top pictures show the banks before coins were inserted, those

in the lower pictures after the coins started the banks in action.

The woodpecker slowly emerges from his birdhouse (in the picture on

the right) when a coin is inserted. Grabbing the coin from the slot, he

suddenly darts back into his house, where, in true woodpecker fashion, he

pecks away at the wall.

___________

(Another in this series will appear tomorrow.)

(Web Note:

Many thanks to Mrs. Edward Early, daughter of William and Lena Roup, for

providing a copy of the above article.)

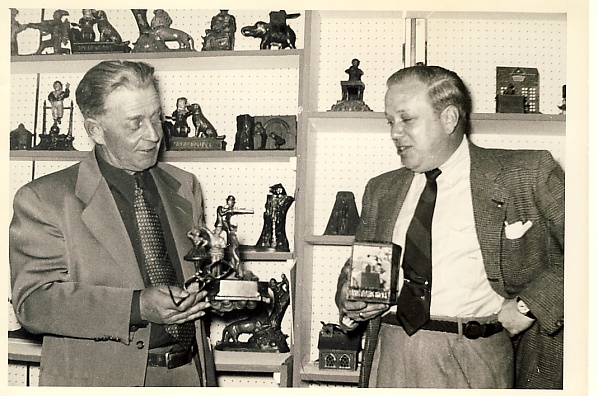

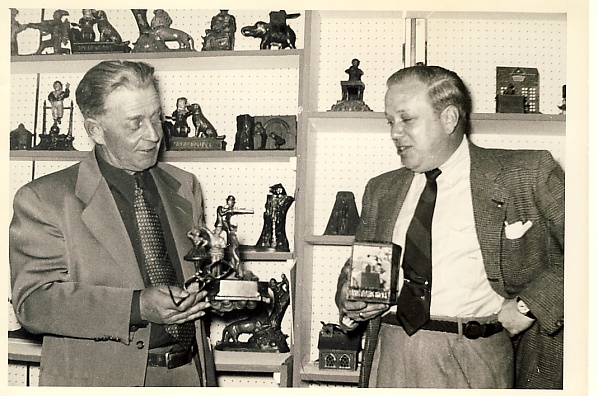

William H. Roup

Lena Roup

William H Roup

and Floyd

H. Griffith

|