By PAT DWYER — Engineering Editor — THE FOUNDRY — May, 1947 — Part 2

Where are the Toy Banks Yesteryear?

This is the second and concluding article on the subject of cast iron toy banks. Illustrations are from the collections of Wilmer H. Cordes, Cleveland, and Andrew Emerine, Fostoria, O. Historical and other data from Cavalcade of Toys, are presented by courtesy of the authors, Ruth and Larry Freeman, Century House, New York.

TO THE average person there is something very pathetic about old toys, either singly or in collections. Faint nostalgic memories of Eugene Field’s "Little Boy Blue" lurk in the background. The little toy dog is covered with rust, yet sturdy and staunch he stands. The little toy soldier is red with rust and the musket molds in his hands. Time was when the little toy dog was new and the soldier was passing fair. That was the time Little Boy Blue kissed them and put them there. The years are many. The years are long **** Aye. Too many and too long.

Worn and apparently useless toys frequently were retained by a fond mother through one generation. Those into whose hands they fell later knew nothing of their origin. There is one comforting thought. The collector who snatched them from the discard is a sympathetic soul and the people who originally loved the dolls and toys, if they were alive, probably would be very glad their cherished possessions had fallen into such good hands.

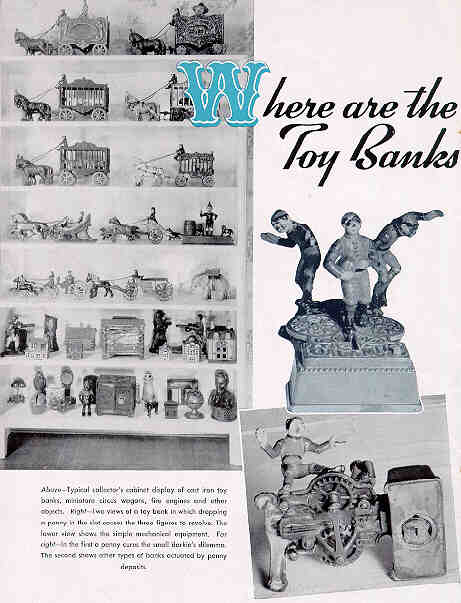

Above — Typical collector’s cabinet display of cast iron toy banks, miniature circus wagons, fire engines and other objects. Right — Two views of a toy bank in which dropping a penny in the slot causes the three figures to revolve. The lower view shows the simple mechanical equipment. Far right — In the first a penny cures the small darkie’s dilemma. The second shows other types of banks actuated by penny deposits.

Back in the so-called good old days, when thrift was cultivated and extolled as a positive virtue and every child was influenced, exhorted and in some instances coerced into saving his or her pennies, several alert inventors sensed an opportunity to turn an honest penny. Shortly afterward several foundries were competing and striving to produce the most attractive and therefore best selling mechanical bank.

These clever and interesting mechanical units were constructed of intricate parts and timed to perform their respective stunts with promptness and precision. They were sold through the general store of the period as toy banks and presented to the boy or girl usually expecting a different kind of a Christmas gift. The first faint apostasy, first heretical whispers touching on the Santa Claus legend seem to have started about this period.

Competent authorities estimate that over 600 different varieties of toy banks were made and of these varieties many thousand banks were sold and distributed between 1875 and 1910. Of this total some 260 models were equipped with moving parts. These became known as mechanical banks to distinguish then from the other styles known as still banks. A large number of the designs were patented as early as 1868 and continuing up to about 1895.

Considering the fact that all early banks were strictly hand made and individually hand painted and decorated, the investigator is truly amazed at the exceedingly low selling price. Mr. Einstein probably could explain this phenomenon as a relatively minor feature of relatively — or something. While he was on the job, perhaps the eminent scientist could explain why foundrymen persistently refuse to blow their own horn regarding the excellence of their product. Also why they stubbornly insist on practically giving away their product, while the manufacturers of other and competing products demand and receive prices that represent a fair exchange for the knowledge and skill, and in many instances the blood, sweat and tears incorporated in the product.

Could Buy a Bank for $1

Coming back to the good old days a customer could go into a toy shop or general store and buy a Circus bank, Dentist, Horse Race, Merry-go-round, Harlequin, Initiation First Degree, Shoot the Chute, or any one of the forty other good banks, done up tastefully in a neat wood carton with name thereon, for a price ranging from $1.25 to $2. Old catalogs issued from 1880 to 1910 list practically all of the old mechanical banks, to wholesale to shop keepers at $8 and $9 per dozen. The shop keeper retailed William Tell, Eagle, ’Spise a Mule, Speaking Dog, Creedmore, Clown on Globe and many others in the same general classification at $1 each. The Tammany bank, Owl, Darkey in Cabin Door, Pig in High Chair, Dog on Turntable and many others sold for 50 to 75 cents each.

Simple still banks made to the approximate image and likeness of wild and domestic birds and animals could be had for the modest price of 5 and 10 cents each. Larger banks representing animals and buildings commanded higher prices, from 25 to 50 cents each. Elaborate specimens in the form of safes with combination locks sold for as high as $1 each. Price of Girl Jumping Rope was $2.50 and the Bulldog Savings Bank — try to rob that one — could be had for the staggering sum of $3.50. Available records seem to indicate that the highest priced bank was the Freedman’s Bank manufactured by Jerome Secor in Bridgeport, Conn., about 1880 and listed in a jobber’s catalog issued by Oscar Strasburger, New York, to sell at $66 per dozen. Naturally the greater number of still and mechanical banks reposing on collector’s shelves today represent the varieties made in immense quantity. The rare and therefore more highly valued specimens are survivors from the designs that for more than one reason or another never went into large production.

Banks of the 1880’s are typified by six examples from the pages of a jobber’s catalog. Animal figures began to come more and more into prominence. The subject of choice was not quite as good as in the preceding decade. In their desire to put out something new, the bank makers were beginning to take second best ideas coupled with more complicated mechanical action. Consider instructions for operating the Bulldog bank: "Place money on his nose, pull tail down and then release, causing three distinct movements — head pulled backward, jaws open and money drops in. After this swallowing of the food placed on his nose, release of the tail pulls the head back to original position ready for another feeding."

In Paddy and His Pig, the penny is placed on the pig’s nose and a lever is pulled. Thereupon Paddy’s eyes roll back, his mouth opens and his tongue licks the penny from the pig’s nose. And what do you think of that Horatio? All for a penny! In the Cabin bank, movement of the whitewash brush causes the negro to stand on his head and kick the coin into the cabin. A very neat bit of drop kicking indeed. The Mirror Multiplying bank has no special mechanical action, but according to the naive description, depends for its appeal upon the optical effect. Then as now, any excuse is good enough to look in a glass. When a penny is given to the teller of a Novelty bank and a lever is pulled the door is closed and the donor may observe through a window the passage of the teller to the place of deposit. The depositor also has the opportunity of bidding his penny goodbye. The Frog on Stump performs a simple swallowing movement. Simple but complete so far as the penny is concerned.

Overlooked One Feature

Typical banks of the 1890’s include the Boy on Trapeze, William Tell, ’Spise the Mule and the Speaking Dog. In the William Tell bank the penny serves for a shot for knocking the apple from the boy’s head. While this bank appeared in the ’90’s, a similar type of shooting bank (Creedmore) had been introduced in an earlier decade. In the Speaking Dog and Mule banks the action for depositing the coin is still fairly direct and simple and undoubtedly would delight a child. All the early makers seem to have overlooked the feature that appeals to all children. Something that makes a loud BANG, rings a bell or blows a whistle. In the Chinese Beggar, a contemporary paper mache bank, the head nods when a penny is inserted. This typifies the German attempt to compete for the American toy market. That it did not succeed is shown by the fact that this foreign bank is a rarity in America.

After 1900 the banks primarily became mechanical toys in which the saving element was very minor. A glance at the pages of manufacturer’s 1906 catalog indicates the over-elaboration which characterized the period. Many of the late mechanical banks were nickel plated. They lacked the naive charm of the earlier cast iron banks with their brightly hand painted exteriors. The Jumping Rope Bank is the ultimate of something or other. In a description of this bank the maker says: "In manufacturing this bank the aim has been to produce a prolonged and continuous performance of its amusing features without the aid of expensive mechanism. This has been accomplished by inventing a simple, strong durable spring motor. The simulation of a skipping rope is perfect. The body, head, feet and rope all moving in unison, but each part performs independently in its own peculiar and appropriate manner." Sounds like a modern sales talk hot off the griddle. In spite of all the shouting and tumult, one has to look for some time before finding the coin slot. In fact this toy could be enjoyed without any vulgar mercenary penny pinching feature. These late banks were not made in any quantity. In some instances it is fairly certain they never passed the sample stage.

It is rather difficult to assign causes for the disappearance of the mechanical bank. One cause may have been the greater popularity of combination safe banks which originated in the late 90’s. Another possible cause lies in the fact that the schools developed special savings plans for the convenience of the boys and girls who happened to arrive with some small change burning holes in their pockets. Banks and trust companies got out their own little satchel like safes which could be opened only at the teller’s window. These met a mixed reception. They were welcomed by the savers and cordially detested by the spenders.

Undoubtedly all these contributed to the decay of a toy and an industry destined from the beginning to be ephemeral or to use a more homely expression, more or less a flash in the pan. Perhaps that expression needs further explanation. Quite a spell since the old flintlock was used. Look it up in the encyclopedia. Practically every hickey, dingus, doodad and gadget was exhausted before mechanical banks disappeared. Looking over a collection of the remaining types one is amazed at the ingenuity displayed in designing so many ways of jiggling the penny before it was swallowed or made to disappear in any other manner.

Worth More Dead Than Alive

Although only approximately 70 years old, mechanical banks already have become a recognized and valuable collector’s item. Banks that sold originally for $1 or $2 in all the glory of red, green and yellow paint, may command up to $100. Curiously enough it is the newest, and not the oldest mechanical banks which sometimes bring these fantastic prices. As with all commodities, scarcity is the principal factor in setting the price. Many of the early banks were highly popular and were sold in large numbers. Made of good old solid and reliable cast iron they withstood all manner of abuse from their deer little owners and are still in the ring, while other and more fragile types of toys have disappeared utterly. As a result of this generous supply or residue, no great value is attached to the common class typified by the Tammany, Cannon and Eagle banks. Hall’s Excelsior, the oldest of them all, can still be had for about $2. Sales are few and noticeably lacking in excitement. In contrast, banks of the 1880-1890 period bring distinctly better prices, in some instances up to $35. The rarest of all banks is a single specimen, probably a sample of a design that never reached the production stage — casualty that reduced the inventor’s already low faith in the taste and perception of the human race.

To understand a situation in which a toy bank, merely a bit of flotsam or jetsam to the ordinary person, can bring a fabulous price, one has to have some knowledge of, or familiarity with, bank collectors. They are relatively few in number, but what they lack in numbers they make up in enthusiasm and acquisitiveness. Their principal object in life is to capture, beg, borrow, steal or in extreme cases — buy objects for which no other collector possesses a duplicate. They are constantly on the alert and in the race. Many of the most enthusiastic collectors are executive officers of banks and large corporations.

Next to his tool box, relic of his young days as a journeyman machinist, the late Walter P. Chrysler valued his elaborate collection of cast iron toy banks. In addition to the pride of possession, he was intrigued by the mechanical movements. Readers of his delightful biography which appeared in the Saturday Evening Post several years ago, will remember the chapter in which he paid tribute to an old boomer machinist in a Kansas roundhouse who showed him how to set the valves in a locomotive.

Where a dealer finds a rare bank it is not uncommon to offer it to several prominent collectors for competitive bidding. These men are not concerned with whether or not the bank was popular with children. They are interested only in whether it is unique, a rare item, and in the mechanical action.

Banks Are In Good Condition

In a general way it may be said that rare banks are newer, in better condition and more elaborate than the older and common varieties. The Harlequin is a good example of a rare bank. Although only a little over thirty years old, its clever design, interesting action and scarcity make it the joy and despair of bank collectors. The bank first appears on the flyleaf of a 1906 catalog, although a similar action was patented in 1887. The Merry-go-round is of slightly earlier vintage, and is considered a very good bank. Bank action is shown at its best and most complex in professor Pug Frog’s Great Bicycle Feat. Release of a spring causes the frog to make two complete somersaults before depositing the coin in a basket held by the clown. Related actions are the spring of the wheel and the throwing of music rack in the face of Mother Goose and causing her tongue to wag. A very clever combination and well worth a penny or several pennies of any person’s money, child or adult.

About 75 percent of the surviving production of mechanical banks in this country is in the hands of 10 or 12 outstanding collectors. All the collections are appraised at high value. Addition of new collectors searching for rare items continually drives the value upward. In the popular language of the day, who would have thought that a partly worn and ancient plaything like a mechanical bank would attain importance enough to be placed in the cabinet of a connoisseur. The mechanical bank is the first toy outside the doll to have reached this popular pinnacle. Dolls have been made in every conceivable shape and material with the possible exception of cast iron. Subject to correction by some lynx eyed reader, it is fairly safe to say no person ever saw a cast iron doll.

Perhaps it is because of its true American flavor that the cast iron bank has had and still has so many enthusiastic friends among collectors. In an idle hour it might be interesting to estimate or speculate on what might happen if and when the fad of collecting other toy types becomes widespread or general.

Few people will deny that children have a natural acquisitive tendency. The quantities of old stones and sticks brought into the play room supply mute evidence. The bank’s success in translating this tendency to the gathering of money is somewhat questionable, at least for the more elaborate banks. Children with no particular desire to save may have thrilled over the mechanical bank, but any container will serve if the child really is in earnest in the desire to collect a bank full of pennies or other coins. Most of the banks referred to in preceding paragraphs really were mechanical toys incidentally devised to encourage thrift in the recipients. Today there is little thrift talk with children and little use for banks. However, the mechanical bank always will remain to delight the collector. It represents 19th century art at the zenith. It is easy to believe that originally many adults bought them to play with. This would not be the first time that adult taste has determined a toy’s ephemeral popularity.